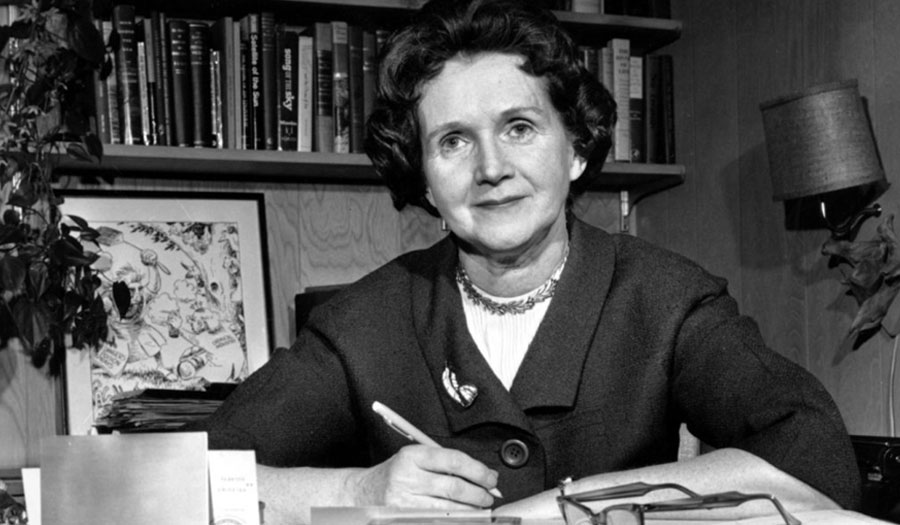

Perhaps the finest nature writer of the Twentieth Century, Rachel Carson is remembered more today as the woman who challenged the notion that humans could obtain mastery over nature by chemicals, bombs and space travel than for her studies of ocean life.

Biologist Rachel Carson alerted the world to the environmental impact of fertilisers and pesticides. Late in the 1950s, Rachel turned her attention to conservation, especially some problems that she believed were caused by synthetic pesticides.

Born in Springdale, Pennsylvania in 1907, upstream from the industrial behemoth of Pittsburgh, Rachel studied Biology, Genetics and Zoology.

She earned a master’s degree in Zoology in 1932 at John Hopkins University. She had intended to continue for a doctorate, but in 1934 Carson was forced to leave Johns Hopkins to search for a full-time teaching position to help support her family during the Great Depression. Sitting for the civil service exam, she outscored all other applicants and, in 1936, became the second woman hired by the Bureau of Fisheries for a full-time professional position, as a junior aquatic biologist and worked primarily as a writer and editor.

Using her research and consultations with marine biologists as starting points, she wrote many articles and published several books about the impact that humans had on the natural world. Her first book was Under the Sea-Wind (1941).

Taking advantage of the latest scientific material for her next book, The Sea Around Us (1951), it became an international best-seller, raised the consciousness of a generation, and made Rachel Carson the trusted public voice of science in America.

Her third book, The Edge of the Sea (1955) focused on the ecosystems of the eastern coast from Maine to Florida.

Her sensational book Silent Spring published in 1962 warned of the dangers to all natural systems from the misuse of chemical pesticides such as DDT, and questioned the scope and direction of modern science.

Diagnosed with breast cancer in 1960, Rachel was undergoing radiation therapy at the time of publication and expected to have little energy to devote to defending her work and responding to critics. So, in preparation for the anticipated attacks, Rachel and her agent attempted to amass as many prominent supporters as possible before the book’s release.

The story of the birth defect-causing drug thalidomide broke just before the book’s publication as well, inviting comparisons between Carson and Frances Oldham Kelsey, the Food and Drug Administration reviewer who had blocked the drug’s sale in the United States.

The chemical companies mounted a fierce campaign to discredit her and her work, questioning her credentials and her personal character, labelling her “…a fanatic defender of the cult of the balance of nature”.

However, the chemical industry campaign backfired, as the controversy greatly increased public awareness of potential pesticide dangers, as well as Silent Spring book sales.

Pesticide use became a major public issue, with the book spurring a reversal in national pesticide policy, which led to a nationwide ban on DDT and other pesticides. It also inspired a grassroots environmental movement that led to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Even in the 1950’s, Rachel’s ecological vision of the oceans shows her embrace of a larger environmental ethic which could lead to the sustainability of nature’s interactive and interdependent systems. Climate change, rising sea-levels, melting Arctic glaciers, collapsing bird and animal populations, crumbling geological faults — all are part of her work. But how, she wondered, would the educated public be kept informed of these challenges to life itself? What was the public’s “right to know”?

Evidence of the widespread misuse of organic chemical pesticides government and industry after World War II prompted her to reluctantly speak out not just about the immediate threat to humans and non-human nature from unwitting chemical exposure, but also to question government and private science’s assumption that human domination of nature was the correct course for the future.

In Silent Spring Carson asked the hard questions about whether and why humans had the right to control nature; to decide who lives or dies, to poison or to destroy non-human life.

Weakened from her breast cancer and treatment regimen, Rachel died in April 1964 in her home. Rachel was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Jimmy Carter.